It is well-known that the curvature properties of Kähler metrics "flow downward".

To give meaning to this statement,

let us say that a tensor \( \alpha \) dominates a tensor \( \beta \)

if any of the following implications hold:

\begin{align*}

\alpha > 0 &\implies \beta > 0,

&

\alpha &\geq 0 \implies \beta \geq 0,

\\

\alpha < 0 &\implies \beta < 0,

&

\alpha &\leq 0 \implies \beta \leq 0.

\end{align*}

Strictly speaking we need to specify what it means for a tensor to be

"positive" or "negative" for this to make sense.

This is fairly clear for the tensors we’ll discuss here, except for the

Kähler curvature tensor itself which we mean to be Griffiths positive (or

negative).

If \( R \) is the curvature tensor of a Kähler metric, its various derived

curvature tensors are the holomorphic sectional curvature \( H \), the Ricci

tensor \( r \) and the scalar curvature \( s \).

Then \( R \to H \to s \) and \( R \to r \to s \),

where an arrow \( \alpha \to \beta \) means that \( \alpha \) dominates \( \beta \).

The witches of the field know that neither \( H \) nor \( r \) dominates the other.

The best evidence for this seems to be indirect.

We for example know that Hirzebruch surfaces (surfaces that are projective

bundles over \( \mathbf{P}^1 \)) carry metrics with positive holomorphic sectional

curvature, but carry no metric of positive Ricci curvature as their anticanonical

bundle is not ample.

There are some suggestive results in the negatively curved case though,

where a compact Kähler manifold that carries a metric of negative holomorphic

sectional curvature also carries a possibly different metric of negative Ricci

curvature.

We don’t know if these are the same metric.

It would be nice if some easy local calculations said they were, but in this note we will see they don’t.

It is also folklore that all of the reverse relations in the diagram fail.

Some do not hold by general considerations; for

example Hirzebruch surfaces

again carry a metric of positive holomorphic sectional curvature but not one of

positive Griffiths curvature, for otherwise they would be \( \mathbf{P}^2 \) by

Siu—Yau’s solution of the Frankel conjecture and, lo,

they are not.

We feel like it would be nice to see explicitly what doesn’t hold here.

In this light reading note we work out local examples that show that the reverse of any known

positivity implication fails.

As other people have noted it would be nice to have compact examples of these

failures but it is fairly difficult to get one’s hands on those.

Suggestions are welcome.

Algebraic curvature tensors

Let \( V \) be a complex vector space of dimension \( n \), which we think of as the

tangent space of a complex manifold at a given point.

The curvature tensor \( R \) of a Hermitian metric on the manifold identifies with

a Hermitian form \( q \) on \( V \otimes V \), defined by

\[

R(x, \overline{y}, z, \overline{w})

= q(x \otimes z, \overline{y \otimes w}).

\]

If the metric is Kähler we get an additional symmetry

\( R(x, \overline{y}, z, \overline{w}) = R(z, \overline{y}, x, \overline{w}) \)

(and the ones induced by conjugating).

We write \( B(V) \) for the real vector space of Hermitian forms on \( V \).

The curvature tensor of a Hermitian metric is then just a member of \( B(V

\otimes V) \).

We’ll call such an element an algebraic curvature tensor, and one that

satisfies the symmetries of a Kähler curvature tensor an algebraic

Kähler curvature tensor.

Proposition

If \( R \) is an algebraic Kähler curvature tensor, then \( R \to H \to s \) and \( R \to r \to s \).

This is both well-known and mostly easily proved by taking traces in an

orthonormal basis.

The trickiest impliciation is to show that \( H \to s \).

Berger gave the original proof by showing that

\[

\frac{1}{\operatorname{Vol} S^{2n-1}} \int_{S^{2n-1}} \!\!\! H(v) \, d\sigma(v)

= \frac{1}{\binom{n+1}{2}} s

\]

by writing \( v = \sum_{j=1}^n v_j e_j \) in an orthonormal basis \( (e_j) \),

expanding the curvature tensor \( R(v, \bar v, v, \bar v) \), and integrating

polynomials in \( v_j \) over the sphere. (The reader who wants to try their

hand at this can see Folland’s paper on integrating polynomials over spheres for the last part.)

Examples of non-dominance in dimension two

Let’s define

\begin{align*}

\mathcal{H}(V)

&= \{ \text{germs of smooth Hermitian metrics on \( V \) at \( 0 \)} \},

\\

\mathcal{K}(V)

&= \{ \text{germs of smooth Kähler metrics on \( V \) at \( 0 \)} \}.

\end{align*}

We just write \( \mathcal{H} \) if \( V \) is clear from context and will usually mean \( V =

\mathbf{C}^n \). Note that \( \mathcal{K} \) and \( \mathcal{H} \) are only convex open cones in real

vector spaces and not full subspaces.

Evaluating the curvature tensor of a metric at \( 0 \) defines nonlinear maps and a

commutative diagram

\begin{align*}

\mathcal{K} &\stackrel{\mathcal{R}}{\longrightarrow} B(\operatorname{Sym}^2 \mathbf{C}^n)

\\

\downarrow & \qquad\qquad \downarrow

\\

\mathcal{H} &\stackrel{\mathcal{R}}{\longrightarrow} B(\mathbf{C}^n \otimes \mathbf{C}^n).

\end{align*}

Both vertical arrows are of course injective.

The horizonal arrows are neither injective nor surjective in general.

Let \( H \) be the matrix of a Hermitian metric \( h \) in a neighborhood around \( 0 \) in

\( V \). The Chern connection of \( h \) is given by \( D^{1,0} = H^{-1}\partial H \) and its

curvature form is

\[

F = \tfrac i2 \bar\partial(H^{-1}\partial H)

= - \tfrac i2 H^{-1} \bar\partial H \wedge H^{-1} \partial H

- \tfrac i2 H^{-1} \partial \bar\partial H.

\]

The curvature tensor is then \( R(x,\overline{y}, z, \overline{w}) = h(F(x, \overline{y}) z, \overline{w}) \).

We can pick coordinates such that \( H = I_n \) at \( 0 \).

If \( h \) is Kähler we can further get \( \partial H = 0 \) at \( 0 \).

We will arrange this in our examples.

We now restrict to \( V = \mathbf{C}^2 \).

Proposition.

The image of \( \mathcal{K}(\mathbf{C}^2) \) in \( B(\mathbf{C}^2 \otimes \mathbf{C}^2) \) is the set of matrices of the form

\[

\begin{pmatrix}

x & a & a & c

\\

\bar a & z & z & b

\\

\bar a & z & z & b

\\

\bar c & \bar b & \bar b & y

\end{pmatrix}

\]

where \( x, y, z \in \mathbf{R} \), \( a, b, c \in \mathbf{C} \).

Proof:

If \( h \) is a Hermitian metric on a neighborhood of \( 0 \) in \( \mathbf{C}^2 \)

we can write it in matrix form as

\[

H = \begin{pmatrix}

a & c

\\

\overline{c} & b

\end{pmatrix}.

\]

After a change of coordinates, we can assume that \( H(0) = I_2 \).

Assuming \( h \) is Kähler we can also arrange that \( \partial H(0) = 0 \).

Then the matrix of the curvature tensor in the basis

\( (\partial / \partial z \otimes \partial / \partial z,

\partial / \partial z \otimes \partial / \partial w,

\partial / \partial w \otimes \partial / \partial z,

\partial / \partial w \otimes \partial / \partial w) \)

is

\[

R = \begin{pmatrix}

a_{z \overline{z}} & \overline{c}_{z \overline{z}} & a_{z \overline{w}} & \overline{c}_{z \overline{w}}

\\

c_{z \overline{z}} & b_{z \overline{z}} & c_{z \overline{w}} & b_{z \overline{w}}

\\

a_{w \overline{z}} & \overline{c}_{w \overline{z}} & a_{w \overline{w}} & \overline{c}_{w \overline{w}}

\\

c_{w \overline{z}} & b_{w \overline{z}} & c_{w \overline{w}} & b_{w \overline{w}}

\end{pmatrix}.

\]

We’ve written, for example, \( a_{z \overline{w}} \) instead of \( \frac{\partial^2 a}{\partial z \partial \overline{w}} \).

The metric \( h \) is Kähler, so we have

\[

a_w = c_{z},

\quad

a_{\overline{w}} = \overline{c}_{\overline{z}},

\quad

b_z = \overline{c}_w,

\quad

b_{\overline{z}} = c_{\overline{w}},

\]

and thus

\[

c_{z \overline{z}} = a_{w \overline{z}},

\quad

\overline{c}_{w \overline{w}} = b_{z \overline{w}},

\quad

c_{z \overline{w}} = a_{w \overline{w}},

\quad

\overline{c}_{w \overline{z}} = b_{z \overline{z}}

\]

Then we get

\[

R = \begin{pmatrix}

a_{z \overline{z}} & a_{z \overline{w}} & a_{z \overline{w}} & a_{w \overline{w}}

\\

a_{w \overline{z}} & a_{w \overline{w}} & a_{w \overline{w}} & b_{z \overline{w}}

\\

a_{w \overline{z}} & a_{w \overline{w}} & a_{w \overline{w}} & b_{z \overline{w}}

\\

a_{w \overline{w}} & b_{w \overline{z}} & b_{w \overline{z}} & b_{w \overline{w}}

\end{pmatrix},

\]

where some simplifications happen because \( a \) is real so \( a_{w \overline{z}} =

a_{z \overline{w}} \) and we can ping-pong to \( b_{z \overline{z}} = a_{w \overline{w}} \).

This is exactly of the form we announced.

We will conclude the proof by taking the above Hermitian matrix as given and

constructing a germ of a Kähler metric whose curvature tensor agrees with it

at \( 0 \).

Suppose we let

\[

f(z,w)

= a_{z \overline{z}} z \bar z

+ a_{z \overline{w}} z \overline{w}

+ a_{w \overline{z}} w \overline{z}

+ a_{w \overline{w}} w \bar w.

\]

Then \( f(0) = 0 \) and \( df(0) = 0 \) and

\[

\operatorname{Hess} f(0)

= \begin{pmatrix}

a_{z \overline{z}} & a_{z \overline{w}}

\\

a_{w \overline{z}} & a_{w \overline{w}}

\end{pmatrix}.

\]

We also let

\[

g(z,w)

= a_{w \overline{w}} z \bar z

+ b_{z \overline{w}} z \overline{w}

+ b_{w \overline{z}} w \overline{z}

+ b_{w \overline{w}} w \bar w

\]

and

\[

h(z,w)

= h_1 z \bar z

+ h_2 z \overline{w}

+ h_3 w \overline{z}

+ h_4 w \bar w.

\]

We want

\[

a_{w \overline{z}} \overline{z} + a_{w \overline{w}} \bar w

= f_w = h_z

= h_1 \overline{z} + h_2 \overline{w},

\]

so we set \( h_1 = a_{w \overline{z}} \) and \( h_2 = a_{w \overline{w}} \).

We also want

\[

a_{w \overline{w}} \overline{z} + b_{z \overline{w}} \overline{w}

= g_z = \overline{h}_w

= \overline{h}_3 \bar z + \overline{h}_4 \overline{w}

\]

so \( h_3 = \overline{h_2} \) and \( h_4 = b_{z \overline{w}} \).

The germ of the Kähler metric

\[

h(z,w)

= \begin{pmatrix}

1 + f(z,w) & h(z,w)

\\

\overline{h(z,w)} & 1 + g(z,w)

\end{pmatrix}

\]

then has the curvature tensor \( R \) above.

Special cases

Let’s look at some special cases. If the tensor looks like

\[

R =

\begin{pmatrix}

x & 0 & 0 & z

\\

0 & z & z & 0

\\

0 & z & z & 0

\\

z & 0 & 0 & y

\end{pmatrix}

\]

and we set \( \xi = (u, v) \) then

\begin{align*}

R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \xi, \overline{\xi})

&= |u|^4 x + 2 (2 |u|^2 |v|^2 + \operatorname{re}(\bar u^2 v^2))z + |v|^4 y

\\

r(\xi, \overline{\eta})

&=

\overline{\eta}^t

\begin{pmatrix}

x + z & 0 \\ 0 & z + x

\end{pmatrix}

\xi

\\

s &= x + 2z + y,

\end{align*}

and the sign of \( R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \xi, \overline{\xi}) \) is the same as the sign of the

holomorphic sectional curvature \( H(\xi) \).

For complex numbers we have \( |\!\operatorname{re} z| \leq |z| \), so we have

\begin{align*}

x |u|^4 + y |v|^4 + 2z |u|^2 |v|^2

&\leq R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \xi, \overline{\xi})

\\

&\leq x |u|^4 + y |v|^4 + 6z |u|^2 |v|^2.

\end{align*}

If further \( u = v \) then

\[

R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \xi, \overline{\xi})

= (x + 6z + y) |u|^4.

\]

Example: \( s \not\to H \)

We can find \( x, y, z \) such that \( x + 2z + y > 0 \) but \( x + 6z + y < 0 \),

(like \( x = y = 4 \), \( z = -3 \)), so the scalar curvature does not dominate

the holomorphic sectional curvature.

Example: \( s \not\to r \)

Take \( x = 4 \), \( y = -1 \) and \( z = -1 \). Then \( x + 2z + y = 1 > 0 \) but

\[

r(\xi, \overline{\eta}) =

\overline{\eta}^t

\begin{pmatrix}

3 & 0 \\ 0 & -2

\end{pmatrix}

\xi,

\]

is neither positive nor negative semidefinite, so the scalar curvature

does not dominate the Ricci curvature.

Example: \( r \not\to H \)

Let \( x = y = 2 \) and \( z = -1 \). Then

\[

r(\xi, \overline{\eta}) =

\overline{\eta}^t

\begin{pmatrix}

1 & 0 \\ 0 & 1

\end{pmatrix}

\xi

\]

is positive-definite, but at \( \xi = (u, u) \) we have

\[

R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \xi, \overline{\xi}) = -4 |u|^4

\]

so the Ricci curvature does not dominate the holomorphic sectional curvature.

Note that the Ricci form is a multiple of the metric, so the metric is

Kähler—Einstein at the origin.

Any statement like ``this metric is Kähler—Einstein so its holomorphic

sectional curvature has a sign'' thus needs more information about the metric

or the manifold to have a chance of being true.

Example: \( H \not\to r \)

We have

\[

R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \xi, \overline{\xi})

\geq

x |u|^4 + 2z |u|^2 |v|^2 + c |v|^4

\]

and the right-hand side is the quadratic form defined by

\[

Q = \begin{pmatrix}

x & z \\ z & y

\end{pmatrix}.

\]

This form is positive-definite if and only if

\[

0 < \operatorname{tr} Q = x + z

\quad\text{and}\quad

0 < \det Q = xy - z^2.

\]

Suppose \( z = -y - \epsilon \) with \( \epsilon > 0 \).

Then

\[

xy - z^2

= xy - y^2 - 2y \epsilon - \epsilon^2

= y(x - y - 2\epsilon) - \epsilon^2.

\]

If \( x > y \), this is positive for small enough \( \epsilon \) (like \( x = 10 \), \( y =

1 \), \( \epsilon = 1 \)).

But then the Ricci form is

\[

r(\xi, \overline{\eta}) =

\overline{\eta}^t

\begin{pmatrix}

x & 0 \\ 0 & -\epsilon

\end{pmatrix}

\xi

\]

which is not positive-definite,

so the holomorphic sectional curvature does not dominate the Ricci

curvature.

Example: \( r \not\to R \)

We have \( \det R = 0 \), because the curvature tensor of a Kähler metric

always has a nontrivial kernel (on manifolds of dimension \( > 1 \)).

It is then enough to pick a metric with \( r \) positive

to get a curvature tensor whose Ricci tensor is positive but is not itself

Griffiths positive.

Otherwise this direction is also covered by the \( r \not\to H \) one.

Example: \( H \not\to R \)

Let \( x = y = 2 \) and \( z = -1 \).

Then

\[

R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \xi, \overline{\xi})

\geq 2 |u|^4 + 2 |v|^4 - 2 |u|^2 |v|^2

= |u|^4 + |v|^4 + { ( {|u|^2} - {|v|^2} ) }^2

> 0

\]

so the holomorphic sectional curvature is positive, but

for \( \xi = (u,0) \) and \( \eta = (0,v) \) we have

\[

R(\xi, \overline{\xi}, \eta, \overline{\eta})

= - (|u|^2 + |v|^2 + u \overline{v} + v \overline{u})

\leq 0

\]

and the inequality can be strict, so the holomorphic sectional curvature does

not dominate the Griffiths curvature.

If \(R\) is the curvature tensor of a Kähler metric, we define its holomorphic

sectional curvature to be

\[

H(x) = R(x, \bar x, x, \bar x) / |x|^4

\]

for nonzero \(x\).

If \( (e_1, \ldots, e_n) \) is a frame of the tangent bundle that is

orthonormal at the center of a coordinate system, we also define the scalar

curvature of \( R \) at the center to be

\[

s = \sum_{j,k=1}^n R(e_j, \bar e_j, e_k, \bar e_k).

\]

A classical result of Berger is that the sign of the holomorphic sectional

curvature determines the sign of the scalar curvature. More precisely he proved that

\[

\int_{S^{2n-1}} H(x) \, d\sigma(x)

= \frac{1}{\binom{n+1}{2}} s,

\]

where \( d\sigma \) is the Lebesgue measure on the sphere normalized to have

volume one. Berger’s proof is by a straightforward calculation that proceeds by

expanding \( H(x) \) in terms of a local frame and then integrating each

polynomial factor over the sphere. There is also a slightly less painful proof

that uses representation theory to compute the integral.

We are going to explain a new, worse, proof of the fact that the holomorphic

sectional curvature determines the sign of the scalar curvature.

The classical proof of Berger’s result is not very illuminating, as it seems to

hinge on the fact that the integrals of \(|z_j|^4\) and \(|z_j|^2 |z_k|^2\)

over the unit sphere agree up to a factor of two.

The representation-theoretic calculation of the integral explains why this happens;

the integral is invariant under such a large group action that the whole thing

has to be the trace, which evaluates to the scalar curvature.

Our new proof offers no explanations, only brute force calculations that work

out, somehow. If we conspire to write

\( R(x) := R(x, \bar x, x, \bar x) \)

then we will show that

\[

\sum_{j=1}^n \hat R(e_j) + \hat R\biggl( \sum_{j=1}^n e_j \biggr) = 2 s

\]

for a different curvature tensor \( \hat R \) whose holomorphic sectional

curvature has the same sign as that of \( R \). Since \( \hat R(x) \) has

the same sign as \( H(x) \), we conclude that the sign of \( H \)

determines that of \( s \).

We’re going to work at the center of a normal coordinate system, so we will pick

an orthonormal basis \((e_1, \ldots, e_n)\) of the tangent space at that point.

If \( (x_1, \ldots, x_n) \) are local coordinates in \( \mathbf C^n \) the torus

\( T^n := S^1 \times \cdots \times S^1 \) acts on \( \mathbf C^n \) by

\[

\psi(x)

= ( e^{it_1} x_1, \ldots, e^{it_n} x_n ).

\]

Given a curvature tensor \( R \) of a Kähler metric, we then define

\[

\hat R(x, \bar y, z, \bar w)

= \frac{1}{(2\pi)^n} \int_{T^n} \psi^* R(x, \bar y, z, \bar w) \, dt_1 \cdots dt_n.

\]

We note some properties of \( \hat R \):

\( \hat R_{jklm} = R_{jklm} \) if \( j=k \) and \( l=m \) or \( j=m \) and

\( k=l \) and is zero otherwise. This is clear by evaluating the integral.

\( \hat R \) has the symmetries of a Kähler curvature tensor, by 1.

\( \hat{\hat R} = \hat R \), by 1.

If \( R(x) > 0 \) for all \( x \) then \( \hat R(x) > 0 \) for all \( x \), because then the integrand is positive for all \( x \) and \( (t_1, \ldots, t_n) \).

The scalar curvatures of \( R \) and \( \hat R \) are equal, because

\(

s = \sum_{j,k=1}^n R_{jjkk}

= \sum_{j,k=1}^n \hat R_{jjkk}

\).

We can explain what \( \hat R \) is:

Recall that a Hermitian curvature tensor on \( \mathbf C^n \) can be viewed as

a Hermitian form on \( \mathbf C^n \otimes \mathbf C^n \), and that such a

tensor has the symmetries of a Kähler curvature tensor if and only if it is the

pullback of a Hermitian form on \( \operatorname{Sym}^2 \mathbf C^n \).

Then \( \hat R \) is just the projection of \( R \) onto the subspace of

diagonal Hermitian forms on \( \operatorname{Sym}^2 \mathbf C^n \).

This way however it’s not so clear that \( \hat R \) also has positive

holomorphic sectional curvature if \( R \) does.

We now note that

\[

\hat R\biggl( \sum_{j=1}^n e_j \biggr)

= \sum_{j=1}^n R_{jjjj}

+ 4 \sum_{j\not=k} R_{jjkk}

\]

and so

\[

\hat R\biggl( \sum_{j=1}^n e_j \biggr)

+ \sum_{j=1}^n \hat R(e_j)

= 2s.

\]

If the holomorphic sectional curvature of \( R \) is positive, then so is the

one of \( \hat R \), and thus \( s > 0 \).

Suppose our job is to design a rate limiting system. It could be embedded in a

service or be a service of its own. Given some details about a request from

which we build a source identifier (an IP address is popular and we may assume

that in what follows) our system should check how many requests have been made

from that identifier in some interval of time and allow or deny the request

based on that information.

I’ve seen a handful of such systems implemented at work. More precisely, I’ve

read outage reports on a handful of such systems. A common theme in their design

seems to be that the system keeps the request count per identifier in some

central database, like Cassandra or MySQL. I can only assume this is done to

ensure the system is in some way fair or correct, where those terms are

taken to mean that as far as we know the rate limits we impose are global across

all requests to a given availability zone or data center or unit of compute

area.

I am but a simple country developer, and am probably missing something obvious,

but it has never been clear to me why we care about fairness or correctness in

these systems. Those come at the price of coordination, which is

evil and we

hate it. But we should also be able to do without it. Each node in our system

can keep its own count of requests per identifier, and make its decisions based

on that local information only.

There are a couple of reasons we can do this. The first is that requests are

presumably load-balanced across our nodes. That load balancing is either done in

as uniform a way as possible, or in a "sticky" way where each request identifier

gets sent to the same node (or small group of nodes, then again as uniformly as

possible). In either case each node sees either zero requests per identifier or

a representative sample of them. So having the nodes make local decisions about

identifiers will in aggregate reflect the global behavior of the system.

The second is that source behavior is usually binary. A given source is either

well-behaved at a given moment, or completely batshit insane. Either behavior is

perfectly visible at the local level and needs no coordination to figure out. If

we need correctness for later accounting or observability, the nodes can report

their local counts to a central authority on their own time.

So the next time you need distributed rate limiting, think locally. Reach for an

in-memory SQLite database, or something horrifying like a ring buffer you roll

yourself and definitely test no part of before shipping. Have fun with it. But

don’t coordinate when you don’t have to.

Let \(V\) be a real finite-dimensional vector space, and let \(\bigwedge^\bullet V\) be the exterior algebra of \(V\).

An inner product on \(V\) induces inner products on each component \(\bigwedge^k V\) of the exterior algebra.

Recall that we have the exterior product

\[

\bigwedge{}^{p} V \times \bigwedge{}^{q} V \to \bigwedge{}^{p+q} V,

\quad

(u, v) \mapsto u \wedge v.

\]

Since all the spaces here are finite-dimensional, there exist constants \(C = C(p,q,n)\) such that

\[

|u \wedge v| \leq C |u| \, |v|

\]

for all \(u \in \bigwedge{}^ p V\) and \(v \in \bigwedge{}^ q V\). Can we estimate these constants?

The answer apparently has applications to physics.

I don’t understand the connection to physics or the physical

motivation, but in a

1961 paper the

physicist Yang

Chen-Ning conjectured that for even-dimensional spaces the optimal

bound is achieved on powers of the standard symplectic form. As

\[

\frac{\omega^p}{p!} \wedge \frac{\omega^q}{q!} = \binom{p+q}p \frac{\omega^{p+q}}{(p+q)!},

\]

where \(\omega = \sum_{i=1}^n dx_{2i-1} \wedge dx_{2i}\) and \(|\omega^p / p!|^2 = \binom np\), the conjecture is that

\[

C(2p,2q,2n) = \tbinom{p+q}p\sqrt{\frac{\binom{n}{p+q}}{\binom np \binom nq}}.

\]

Yang claims to prove this for the case of \(p = 1\) in his 1961 paper, though I don’t understand his proof.

A preprint from 2014 claims to prove more cases of the conjecture; again the details of the proof defeat me.

There are two ways of getting rather brutal estimates for these constants.

Let \((v_1, \ldots, v_n)\) be an orthonormal basis of \(V\).

Then \( (v_I) \) where \(I \subset \{1, \ldots, n\}\) with \(|I| = p\) is an orthonormal basis of \(\bigwedge^p V\), and similar for \( (v_J) \) with \(|J| = q\).

If \(u\) and \(v\) are elements of these bases, then \(u \wedge v\) is either 0 or has norm 1.

For our first attempt, let \(x = \sum_{|I|=p} x_I v_I\) and \(y = \sum_{|J|=q} y_J v_J\) be elements of \(\bigwedge^p V\) and \(\bigwedge^q V\).

Then

\[

|x \wedge y|

=

\biggl|

\sum_{|I|=p, |J|=q} x_I y_J v_I \wedge v_J

\biggr|

\leq

\sum_{|I|=p, |J|=q} |x_I y_J|

= \sum_{|I|=p} |x_I| \cdot \sum_{|J|=q} |y_J|.

\]

By taking the inner product of \(x\) and the vector whose elements are the signs of each \(x_I\) and applying Cauchy—Schwarz, we get

\[

\sum_{|I|=p} |x_I| \leq \sqrt{\tbinom np} |x|.

\]

This gives

\[

|x \wedge y| \leq \sqrt{\tbinom np \tbinom nq} |x| |y|.

\]

Our first estimate is thus \(C(p,q,n) \leq \sqrt{\binom np \binom nq}\).

This is likely to be a bad estimate, because when applying the triangle inequality above we assigned equal weight to all expressions \(|v_I \wedge v_J|\), even though many of them were zero.

We also applied the Cauchy—Schwarz inequality on top of the triangle one.

The conditions for those inequalities to be exact are orthogonal — the triangle one is exact when all the vectors lie on a straight line, while Cauchy—Schwarz is exact when all the vectors are orthogonal — which should yield suboptimal bounds.

For our second attempt, we consider the bilinear map

\[

b : \bigwedge{}^ p V \otimes \bigwedge{}^ q V \to \bigwedge{}^ {p+q} V,

\quad

u \otimes v \mapsto u \wedge v.

\]

Its operator norms satisfy \(\|b\|^2 \leq |b|^2\), where

\[

\| b \|^2

= \sup_{x,y} \frac{ |b(x,y)|^2 }{ |x|^2 |y|^2 }

\]

and where \(|b|\) is the Hilbert—Schmidt norm. We can calculate that norm by counting the number of non-zero entries in the matrix for \(b\).

Let then \(I = (i_1, \ldots, i_p)\) be a multiindex. We can choose \(\binom{n-p}{q}\) indices \(J = (j_1, \ldots, j_q)\) such that the corresponding basis elements \(v_I\) and \(v_J\) satisfy \(b(v_I \otimes v_J) = v_I \wedge v_J \not= 0\). As there are \(\binom np\) ways of picking \(I\), we conclude that the Hilbert—Schmidt norm of \(b\) is

\[

|b|^2 = \tbinom np \tbinom {n-p}q = \tbinom n{n-p} \tbinom {n-p}q.

\]

We then get a slightly better estimate

\[

C(p,q,n)

\leq \sqrt{\tbinom n{n-p} \tbinom {n-p}q}

\leq \sqrt{\tbinom np \tbinom nq}

\]

with equality in the second place if and only if \(p = 0\) or \(p = n\).

A fun fact is that these estimates are arbitrarily bad.

When \(p + q = n\), the Hodge star operator gives an isometry \(\bigwedge^q V \cong \bigwedge^p V\) and the Cauchy—Schwarz inequality gives

\[

|u \wedge v| \leq |u| |v|,

\]

so \(C(p,n-p,n) = 1\), which agrees with Yang’s conjectured value when \(p\) and \(n\) are even.

Our best estimate in this case is

\[

C(2p,2n-2p,2n) \leq \sqrt{\tbinom {2n-2p}{2p}},

\]

which goes to infinity as \(n\) grows.

I think this is a very fun instance of a problem that’s easy to state and whose solution is somewhat difficult. The simple attempts at a solution run into basic problems with the optimal conditions for different inequalities on the one hand, and the fact that the things we can easily calculate are not the things we’re interested in on the other hand.

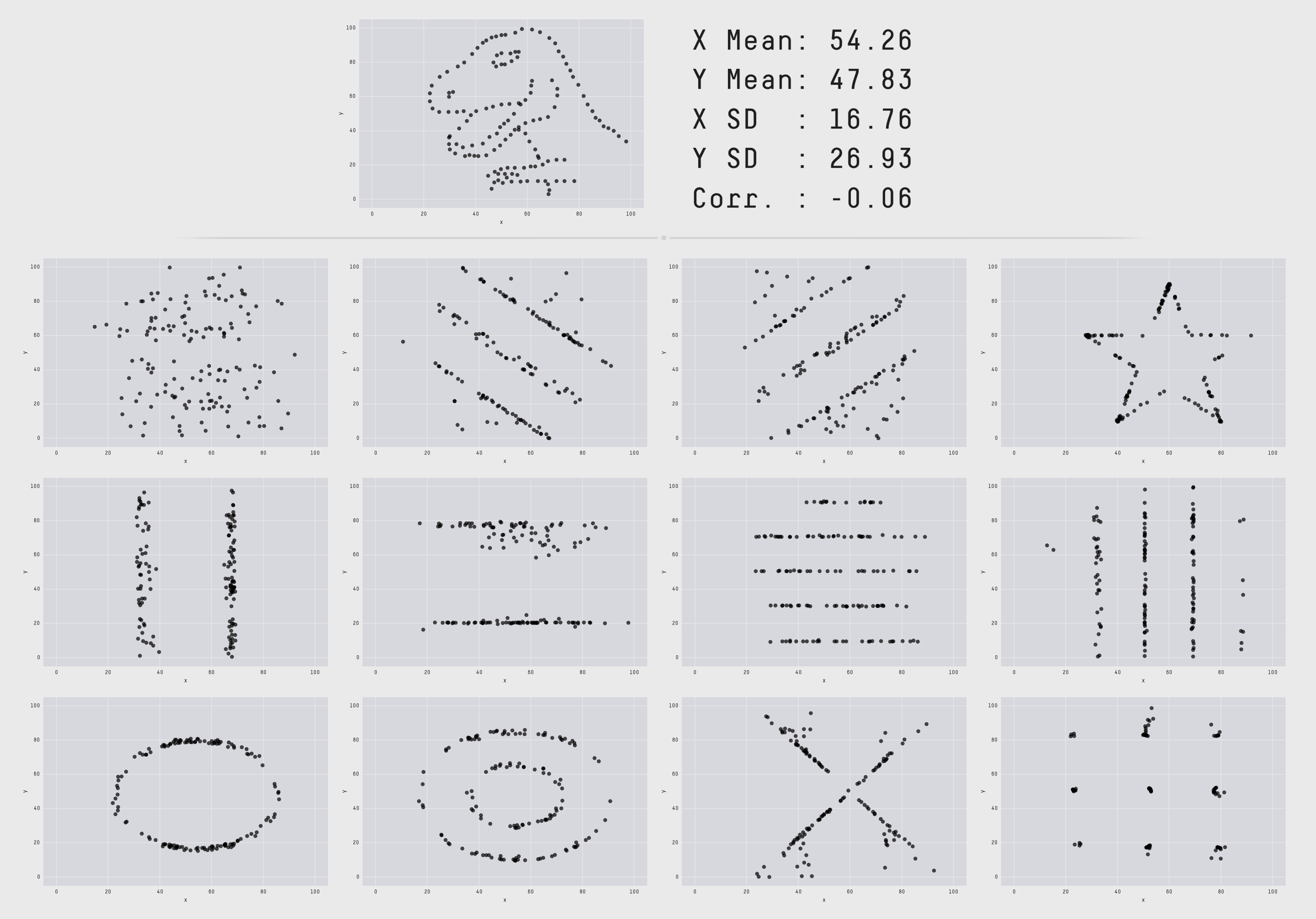

Anscombe’s quartet is a collection of four data sets of points in the plane. When graphed the data sets are obviously very different, but they have identical sets of descriptive statistics. Newer variations on the same theme include the delightful Datasaurus dozen, which includes animations of deformations from one step into another where the descriptive statistics are kept identical during the animation.

I’ve seen Anscombe’s quartet cited in discussions around monitoring and

observability to assert that the average and standard deviation (two of the

statistical tools used in the quartet) are not useful for monitoring and

alerting; instead one should use percentiles. I agree with the conclusion but

think it does not follow from the premise, and would like to offer some thoughts on the theme from the perspective of a reformed geometer.

To do so, I’d like to work out some examples involving the average and standard deviation. The data sets above involve collections of points in the plane but I’d like us to discuss data modeled on timeseries instead. The difference isn’t important, everything we say applies to both theaters, but the geometry we want to point out is easier to see in the latter.

Setup

We’ll model a portion of a timeseries as a tuple of \(n\) real numbers \((x_1, \ldots, x_n)\). We can think of these as \(n\) measurements recorded at one-second (or minute, hour, …) intervals. The set of all possible such timeseries is familiar; it is the real vector space \(\mathbb{R}^n\) of dimension \(n\). (Timeseries can be added and subtracted, there is a zero-timeseries that serves as an identity, and we can multiply a timeseries by a real number.)

The main characters of our story are the average and standard deviation. If \(x = (x_1, \ldots, x_n)\) is a timeseries, its average is

\[

\mu(x) = (x_1 + \cdots + x_n) / n

\]

and its standard deviation is defined by the scary formula

\[

\sigma(x) = \sqrt{ ( (x_1 - \mu(x) )^2 + \cdots + (x_n - \mu(x) )^2 ) / n }.

\]

We can now look at some examples. In every one of these, we’ll fix the average and standard deviation to some values and look at the collection of timeseries that have those values. The first couple of examples are just warm-up.

n = 1

We first look at \(n = 1\), that is, timeseries that just have one value \(x = (x_1)\). For such a timeseries we have \(\mu(x) = x_1\) and \(\sigma(x) = 0\) so each timeseries is uniquely determined by its average and they all have the same standard deviation.

n = 2

The next case is \(n = 2\), of timeseries with two values \(x = (x_1, x_2)\). This is slightly more interesting; we have the average \(\mu(x) = (x_1 + x_2) / 2\) and the standard deviation

\[

\begin{align}

\sigma(x)

&= \sqrt{( (x_1 - \mu(x) )^2 + (x_2 - \mu(x) )^2 )/2}

\\

&= \sqrt{((x_1 - x_2)^2 + (x_2 - x_1)^2)/8}

= |x_1 - x_2|/2.

\end{align}

\]

The second equality here is by substituting the definition of \(\mu(x)\).

This is more interesting because different timeseries can have different

averages and standard deviations. However, I claim that if we fix both the

values of the average and standard deviations, say to \(\mu\) and \(\sigma\),

there is at most one timeseries that has those values.

To see this, observe that the formula for the average implies that \(x_2 = 2 \mu - x_1\), so if we fix the value of the average the value of \(x_2\) is determined by the choice of \(x_1\). If we substitute this into the formula for the standard deviation we get

\[

\sigma(x) = |x_1 - 2 \mu + x_1|/2

= |x_1 - \mu|.

\]

We can solve this equation by splitting into cases where \(x_1 > \mu\) and \(x_1

< \mu\). In the former we get \(x_1 = \sigma + \mu\) and in the latter we get

\(x_1 = \mu - \sigma\). Notice that in both cases, the value of \(x_1\) is

determined by the values of the average and standard deviations, and the value

of \(x_2\) is determined by that of \(x_1\) and the average, so both \(x_1\) and

\(x_2\) are determined once we fix the others.

n = 3

We now get into the first case that has a hint of the general picture. Our timeseries have three points, \(x = (x_1, x_2, x_3)\). We could write down equations like in the previous case and calculate, but it’s worth it to take a step back and think about what’s going on.

Let’s say we have fixed the value of the average of our timeseries to a constant \(\mu\). The formula for the standard deviation of our series is then

\[

\sigma(x) = \sqrt{((x_1 - \mu)^2 + (x_2 - \mu)^2 + (x_3 - \mu)^2)/2}.

\]

If we form the point \((\mu, \mu, \mu)\), we see that

\[

\sigma(x) = \|(x_1, x_2, x_3) - (\mu, \mu, \mu)\|/\sqrt{2}

\]

is just a multiple of the Euclidean distance between our timeseries and the fixed point \((\mu, \mu, \mu)\). If we also fix \(\sigma(x) = \sigma\), the set of points that satisfy this equation is

\[

S := \{ (x_1, x_2, x_3) \mid \|(x_1, x_2, x_3) - (\mu, \mu, \mu)\| = \sqrt{2} \sigma \}.

\]

This should look familiar, it is the sphere whose center is \((\mu, \mu, \mu)\) and whose radius is \(\sqrt{2}\sigma\).

Similarly, the set of timeseries whose average is equal to \(\mu\) is

\[

P := \{ (x_1, x_2, x_3) \mid (x_1 + x_2 + x_3)/2 = \mu \}.

\]

For those who know a little linear algebra, we can write the condition as being that \((x_1, x_2, x_3) \cdot (1, 1, 1) = 2 \mu\), that is, that the inner product with \((1, 1, 1)\) must be equal to \(2 \mu\). The set of points that satisfies such a condition is a plane; a flat two-dimensional space.

We’re interested in the set of points where both of these conditions are true,

which is the intersection \(S \cap P\). We could work out what that is by

calculation, but it’s easiest to visualize it. The intersection of a sphere and

a plane in three dimensions is either empty (when they don’t meet), a single

point (when the plane is tangent to the sphere), or a circle that lies on the

sphere.

In three dimensions, if we pick our values for the average and standard deviations right, there is thus a whole circle of timeseries that have that average and standard deviation. They form a kind of Anscombe set.

Higher dimensions

In higher dimensions, basically the same thing happens as in dimension 3. The set of timeseries that have a fixed average is a hyperplane and the set of timeseries that have a fixed standard deviation and average is a sphere. Their intersection, when it is not empty or a single point, is not as easily described but it is a subspace of dimension \(n-2\). As \(n\) grows higher, this space grows as well, and in general the space of timeseries that have a fixed average and standard deviation is enormous.

Other prescriptive statistics

The final point I’d like to make, and one you’ll have to take my word for to some extent, is that there is nothing special about the average or standard deviation here. Very similar things will happen for every collection of statistical tools we pick.

Every statistical tool can be viewed as a function that takes a timeseries (or perhaps a couple of timeseries, which complicates things a little but not a lot) and returns a real number. These functions are very well behaved (continuous, differentiable, and so on).

Given a collection of such functions \(f_1, \ldots, f_k\) on the space of timeseries of \(n\) points, we can ask whether there is an Anscombe set of fixed values of these functions? That is, if we fix values \(y_1, \ldots, y_k\), can we say anything about the set \(\{x = (x_1, \ldots, x_n) \mid f_1(x) = y_1, \ldots, f_k(x) = y_k \}\)?

With some hand waving, we can actually say this: Fixing the value of a single

tool \(f_j\) creates a hypersurface \(X_j = \{x \mid f_j(x) = y_j\}\) inside the

space of timeseries, that is, a subspace of dimension one less than the ambient

space. All timeseries in \(X_j\) will have the same value with respect to this tool. If the intersection of all of these \(X_1 \cap \cdots \cap X_k\) is not empty, it will generally be a subspace of dimension \(n - k\). If \(n\) is much bigger than \(k\), the dimension of this space, the space of timeseries that all have the same statistical values with respect to our tools, is enormous.

Making the hand waving precise and figuring out when this intersection will be non-empty is the domain of algebraic geometry over the real numbers. Saying anything at all about that is beyond our scope here.

Outro

I hope I have convinced you that the statement "the average and standard deviation are useless for monitoring because of Anscombe’s quartet" is not true. The moral of Anscombe’s quartet, which boils down to intersection theory in algebraic geometry, is that the space of data that fits any given collection of statistical instruments (including any collection of percentiles) is gigantic and we have to look at the data to make sense of it.

In general, percentiles are more valuable for analyzing performance or traffic data than the average and standard deviation. The reason is not Anscombe’s quartet, the robustness of percentiles, or anything to do with normal distributions, but that the average and standard deviation are fundamentally tools for answering the questions "what would this be if it were constant?" and "how far away is this from being constant?". For performance and traffic analysis, we don’t care about either of those questions, but about peaks in demand and how we can handle them. We should pick tools that can help with that, but other tools have their place.

The trolley problem asks how to decide between the lives of people in two groups. At the moment, it comes up in our industry in discussions around self-driving cars: Suppose a car gets into a situation where it must risk injuring either its passengers or pedestrians; which ones should it prioritize saving?

Always choosing one group leads to suboptimal outcomes. If we always save the pedestrians, they may perform attacks on car riders by willfully stepping into traffic. If we always save the passengers, we may run over a pedestrian whose life happens to be of greater worth than that of the passengers.

The crux of the trolley problem is how we should make the choice of what lives to save. As with all hard problems without clear metrics for success, it’s best to solve this by having the participants decide this for themselves.

Every time we view a website, our friendly ad networks must decide what ads we should see. This is done by having our user profile put up on auction for prospective advertisers. During a handful of milliseconds, participants may inspect our profile and place a bid for our attention according to what they see.

The same technology could be trivially repurposed for deciding the trolley problem in the context of self-driving cars.

Assume the identity of every participant in the trolley scenario is known. Practically, we know the identity of the passengers; that of the pedestrians could be known if their phones broadcast a special short-range identification signal. An incentive for broadcasting such a signal could be that we would have to assume that a person without one were one of no means.

Given this information, a car about to be involved in a collision could take a few milliseconds to send the identities of the people involved to an auction service. Participants who had the foresight of purchasing accident insurance would have agents bidding on their behalf. The winner of the bid would be safe from the forthcoming accident, and their insurance would pay some sum to the car manufacturer post-hoc as a reward for conforming to the rules.

The greater a person’s individual wealth, the better insurance coverage and latencies they could purchase, and the more accidents they could expect to survive. This aligns nicely with the values of societies like the United States, where the worth of a person’s life is proportional to their wealth.

As this system lets self-driving car manufacturers off the hook for any decisions taken, and would need coordinated ethical action on the behalf of software engineers to not be implemented, we expect to see this system in action in the world in short order.

I’m pleased to announce the release of my new card-drawing game Infosec.

The rules of the game are simple. It is for two or more players. The player with the fewest friends is the Infosec Expert; the other players are the Coworkers.

To start, the Infosec Expert deals three cards face down from a standard deck of cards. The Coworker on the Infosec Expert’s right hand should draw one card.

"Which card?" the Coworker may ask.

"This is a simple phishing exercise," the Infosec Expert should reply. "Just pick a card."

"But they all look the same," the Coworker may object.

"Draw one. And get it right."

This exchange should go on in increasingly hostile tones until the Coworker agrees to draw a card. It will have been the wrong card. The Infosec Expert should inform the Coworker:

"You got phished. You moron. You fucking idiot. You’re such a goddamn waste of space and time. How could you have gotten this so wrong? Were you even trying? Answer me. What the fuck was that?"

Feel free to ad-lib along these lines, or draw as many cards as you want from the accompanying Admonishment Deck (expansion packs available). Include ad-hominem attacks and use as many personal details as you know. Interrupt the Coworker if they try to reply. Don’t hold back.

Once the Coworker is silent, the Infosec Expert should collect the cards, deal new ones, and proceed to the next Coworker in line.

The game ends with the Infosec Expert’s victory when all the Coworkers have left.

Like so many things I’m supposed to do but don’t — getting exercise, eating right, sleeping well, standing up for women and minorities in public spaces — backing up my data has always been something I’ve half-assed at best.

I’ve lugged around an external hard drive with a few hundred gigabytes of data for the last 10 years, and made backups to it once every three or four years or so. Every time I’ve tried restoring anything from those backups I’ve regretted it, because of course I just bought the drive, plugged it in and copied stuff to it, so it is a FAT32 drive while I have mostly had EXT4 filesystems, which means all my file permissions get lost during the process.

I’ve written shameful little shell scripts to set file permissions to 0644 and directory permissions to 0755, recursively, many many times.

Part of my problem was that I both know just enough rsync to be dangerous and have a credit card so I can provision cloud VMs, so forever just around the corner was my perfect backup solution that I’d write myself and maintain and actually do instead of dealing with whatever I had going on in my life. I’ve come to accept that this will never happen, or perhaps more definitively, that I’d rather cut myself than write and maintain another piece of ad-hoc software for myself.

Luckily I recently found two things that have solved this whole problem for me: borg and rsync.net.

Borg is backup software. It compresses and deduplicates data at the block level, and strongly encourages (but does not force) you to encrypt data before backing it up. It is everything I’d want from my half-assed rsync and shell script abomination.

I read its documentation a couple of times and was impressed. I then set about comparing different VM hosts to see which one would give me the cheapest block storage option, when the result of some random google search led me to rsync.net. They are a company that stores backups, pretty cheaply, and even more cheaply if you use borg to take them. I guess they just really love borg and want us to love it too.

I signed up for their cheapest plan, which starts at 100GB stored for $18 per year. They have no network in- or egress costs, and the storage amount can be adjusted at any time. Once my account had been activated, I did a little password reset dance, and uploaded a public SSH key.

I wanted to back up my $HOME directory, so after installing borg I ran:

export BORG_REMOTE_PATH="borg1"

borg init --encryption repokey-blake2 UID@ch-s011.rsync.net:home

This created a remote borg repository called "home" on rsync.net’s servers. The environment variable is so we use a more recent version of borg on the remote server (version 1.1.11 at the time of writing), as the default version is rather old (version 0.29.0).

When choosing what encryption method to use, one can choose between a "repokey" or a "keyfile". They both create a private key locked with a passphrase; the difference is that with "repokey" the key is stored in the borg repo, while with "keyfile" it is stored outside of it. This boils down to whether we think a passphrase is enough security for our data, or whether we think having a secret keyfile is necessary. I figured my password manager could create a strong enough passphrase for my needs, and I didn’t want to think about losing the keyfile, so I chose "repokey-blake2".

To create my first backup, I ran

borg create --exclude "$HOME/.cache" UID@ch-s011.rsync.net:home::backup-1 "$HOME"

which created the archive "backup-1" in my "home" borg repository. I didn’t change the compression algorithm from the default one.

By default borg compresses data with lz4. It can use other compression methods (xz, zlib, zstd). I compared their compression ratios on some binary files I had and found no difference between them. I think this is because the large binary files I have are mostly audio and video files in lossy formats, which don’t seem to benefit very much from further compression. I have a lot of text files as well, but text takes up so little relative space on today’s hardware that it makes no sense to spend CPU cycles on compressing it better than lz4 does.

This backup command hummed along for a good while, and through a couple of reboot cycles. Doing a second backup right after it finished (or the day after) took a lot less time because of the deduplication:

borg create --exclude "$HOME/.cache" UID@ch-s011.rsync.net:home::backup-2 "$HOME"

Restoring from backup is also easy:

borg extract UID@ch-s011.rsync.net:home::backup-2

I set this up to run as a daily timed systemd service at noon (very easy on NixOS, which every Linux user should be using unless they hate themselves), and will never, ever think about this again. For a handful of bucks a year, that is a good deal.